What do you do with your photography. Do you keep most of it on a hard drive, or do you hang choice works on the wall? I believe the more ways you can use photography, the more people can appreciate it. One of my favorite ways to showcase my photography is to create books with it.

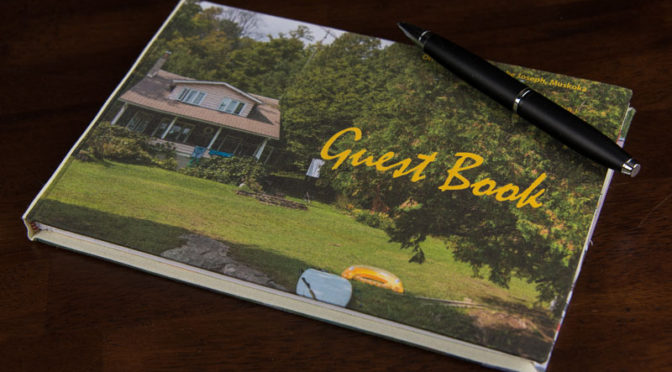

Have you ever noticed lots of places have a guest book? And almost all of them are basically generic guest books that someone got from a stationery store. No customization. No personalization. No reflection of the owner other than classy, cute, wedding, or anniversary.

I believe guest books should reflect the personality of the owner and be customized to the location or event they are to be used in. They should be built to last, as they will be, if not an heirloom, then at least a memento of that place or time.

For a cottage guest book, I take a picture or two of the site, which will be used on the covers and as a watermark on every page of the book. There are the standard lines for people to write on, but I add custom headings the owner will want. I hand sew the book with archival materials and techniques for longevity, so the guest book can be an heirloom to be passed down through the generations. Or not.

If you read the May 16, 2016 blog, Bookbinding Introduction, you know six different binding methods that the local print shop can do for you, or if you invest in the equipment, you can do yourself.

This week, I’ll be walking through the process of hand binding a hardcover guest book. It’s an overview, so not all of the steps are fully explained. If it piques your interest and you think you’d want to hand sew a binding yourself, I highly recommend the bookbinding courses offered by Canadian Bookbinding and Book Artists Guild (CBBAG), especially Bookbinding I. See their website, https://cbbag.wildapricot.org/

Either way, here’s what I do.

Because I do this regularly and I have a copy of Adobe InDesign, I created a template. The photographs are set in a master page. Whatever is included in a master page shows up on every page that references that master. There can be several different master pages, but for a guest book, I usually just have one. Let’s call it A-Master.

To give the watermark appearance required for people to write on top of a photograph, I set the opacity to 10%. I also include the property name (if the cottage has one), the address and the lines the guests will be writing on with information headings they should fill in. The page number is also included. Every guest book page thereafter references A-Master, and has all of that content included. Since a guest book consists of little else, all that remains is to add a title page, the copyright page, and if wanted, a page or two of introductory information.

To reduce the costs of the book, I print it at my local Staples on a mat-finished card stock weight of paper. The standard office paper is about 24 lbs. I use 65 lbs or more, because a book looks best if you can’t see the writing on the other side of paper. A guest book, also has the complication that you have little control over what kind of pen and ink will be used to write in it and you want to reduce the chance that whatever they use won’t bleed through to the other side. Also, some pens don’t write well on glossy paper, so I use a mat finish in my guest books.

You can send a document to your printer in Adobe PDF format just as you would any other document, and they can turn it into a 4-up page layout for you, for a price. Because I’m a control freak, I prefer to do that myself so I know exactly what the pages are going to look like before they go to the printer, and I don’t have to fret that the printer might do something I don’t want.

I have a cool little add-in for InDesign called Imposition Plug-in. It’s by a company called Imposition Software and it only costs about $40 USD, so currently about $60 CDN. You’re dying to know why it’s called “Imposition” because it sounds a little rude, but it’s not (I should know, I’m Canadian). The process of reformatting a document into printing plates is called “imposition” so if you want something a printer would use, it’s best to use the term they’d use.

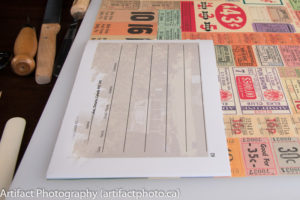

So, when the document comes back from the printer, you will notice there are two copies of two different pages on every face of every page. I like to hedge my bets, so I create two copies of every book and I give the best one to the client. That leaves me with one I can show other potential clients, and I when I don’t need it anymore, if it still looks undamaged, I can sell it to the client at a reduced rate, or perhaps give it to them as a “remember me?” thank you gift. Note: The address on each page has been intentionally disrupted as the client requested anonymity.

At this point, I sense I should go over the tools of the bookbinding trade.

In the photograph above, starting in the top left corner:

- Stabbing cradle to align pages and awl to create holes for sewing

- Brick wrapped in paper used as a weight

- Masking tape

- Brass cutting shield protects paper under it from blades cutting paper on top of it

- Slicing knife for cutting folded paper

- Scalpel for precision cutting

- Box cutter used for most cutting

- Cork to protect everything from the scalpel’s blade

- Sandpaper for sanding edges of cut cover boards

- Notebook and pencil for calculating layout and cutting patterns

- Square for aligning cover boards

- Bone folders (3) for folding paper (not bones)

- Dividers for measuring thickness of various components

- Ruler for measuring stuff

- Brass – four common sizes for quick alignment 1/4″, 1/2″, 3/4″, and 1″

- Needle and thread for sewing paper together

Not shown are other items, such as a cutting board, scrap paper, paste brushes, measuring cups, etc.

And, of course, a book press.

Back to the task at hand.

As mentioned at before the tools, the sheets come back from the printer with seemingly random pages side by side, one copy above the other. All will become apparent shortly.

Separating the Spreads

The first task is to separate the upper copy from the lower copy. It’s probably wise to tell you that the name for two pages side by side is a “spread.” I didn’t come up with it, it’s just what they’re called.

So, I fold the page in half so that the two spreads are stacks precisely above one another. I use a bone folder to make the fold crisp.

Then I use a slitting knife to cut the top signature from the bottom. I do this for all 16 sheets.

I fold each spread in half, so that I wind up with a pamphlet with a page on each face of the paper, making sure that the page number on the top sheet is less than the pages on the inside and rear of the pamphlet. As each spread is folded, I slide higher numbered pages inside the first set, until the entire group of four sheets consists of 16 consecutive pages.

Then you have another set of four sheets to fold and collate. Each of these sets of four sheets is called a “signature”. With a 64 page guest book, you should wind up with four signatures. But wait, I’m not done!

The four signatures are the content of the book, but you also need two spreads at each end of the book for end papers. These are usually different coloured papers (to look fancy) which are sewn into the text block (the collection of signatures) and glued to the cover. They form part of the hinge. I either use two identical sheets of a fancier paper, or one fancy and one printed paper for the inside of the cover. They are exactly the same size as the other spreads in the text block. So if you’ve ever wondered why there are two blank pages after the cover in a hardcover book, you now know.

Stabbing the Signatures

You have your end papers and your content signatures. How do you sew them? First, you have to stab them in the cradle. This lets the needle go through with the least fuss. But you don’t just stab them randomly. You have to be organized. I take a piece of scrap paper and cut it to match the length of the spine of the signatures. I fold it lengthwise so it looks like a narrow page of the signature. Then I fold it in half from top to bottom, and fold it in half again. This gives me a piece of paper with three folds. I unfold it, and this indicates where the linen tapes will be going.

The linen tapes will be holding the text block to the hinge of the cover. There will be three of them. I measure the width of the tape is the dividers and I mark holes on either side of each fold on the piece of paper.

I then use the dividers to measure a piece of headband (not the things we wore in the 70’s). Headbands are those colourful threads at the top and bottom of expensive bound books. The don’t actually do anything other than look pretty, but we want them. I measure the width of the headband and mark that on the paper at the top and bottom. I choose an end of the paper to call the head, and mark it with an arrow. This will be used to align all signatures to the top.

I open the first signature (the end papers) in the V of the cradle and align it against the end of the cradle marked “head”. I put the template I just made into the centre of the V on top of the open signature and align the arrow I just marked at the end of the cradle marked “head”. I carefully stab the paper and the signature at the marked points with the awl and voila! I have a signature ready for sewing. I do the same thing with all of the other signatures and then I have a text block ready for sewing.

Sewing the Text Block

I start by putting one of the end paper signatures down on my cutting board. You can get or build a proper sewing frame, but I don’t have one and haven’t built one yet. I expect when I do get around to it, I’ll wonder how I got along without one. But, instead, I tape one of the linen tapes to the edge of my cutting board, and line the signature holes up so that the first pair of holes past the end band holes surround the linen tape. I then tape the next linen tape to line up with the next set of holes, and finally, the last linen tape to line up with the last set of holes.

I put a nice three or four foot length of 18/3 linen thread through the head of a needle, and start sewing.

I start by going in on one of the end band holes, and back out at the first linen hole. Without sewing through the linen tape, I go back into the next linen hole, out at the next, in at the next, out, in, and finally out at the last end band hole. I put the next signature in place, ensuring that the top is at the top and the bottom is at the bottom. Otherwise, it gets frustrating when you inspect it and discover you have to cut the thread and sew it again.

From the first signature, I go in the adjacent linen hole on the second signature, out at the next hole, in, out, in, out… you get the picture. The idea is to sew the binding tightly, but not so tightly that the book looks like a banana.

When I get to the end of the second signature, I swoop down and link (wrap once around) the thread going into the first hole in the first signature and go up to the first hole in the third signature. In, out, in, out…until done.

Next week, in Part 2, I’ll show how the text block is connected to the cover. Then I’ll get back to photography, I promise.

This blog is published every Monday at 9:00 am, Eastern Standard Time. If you have comments, questions, or can think of a better approach, feel free to leave a comment. I’ll try to get back to you with a pithy answer.

Feel free to explore the rest of the Artifact Photography (a division of 1350286 Ontario Inc.) website at www.artifactphoto.ca